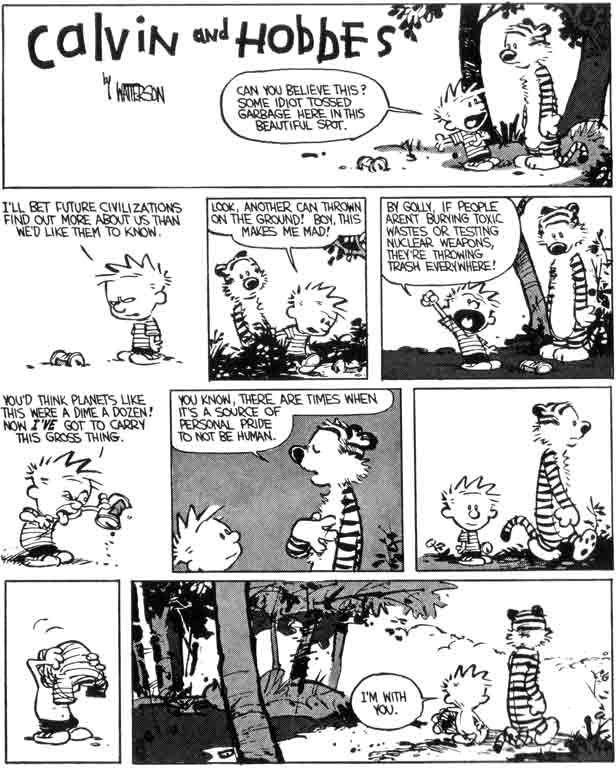

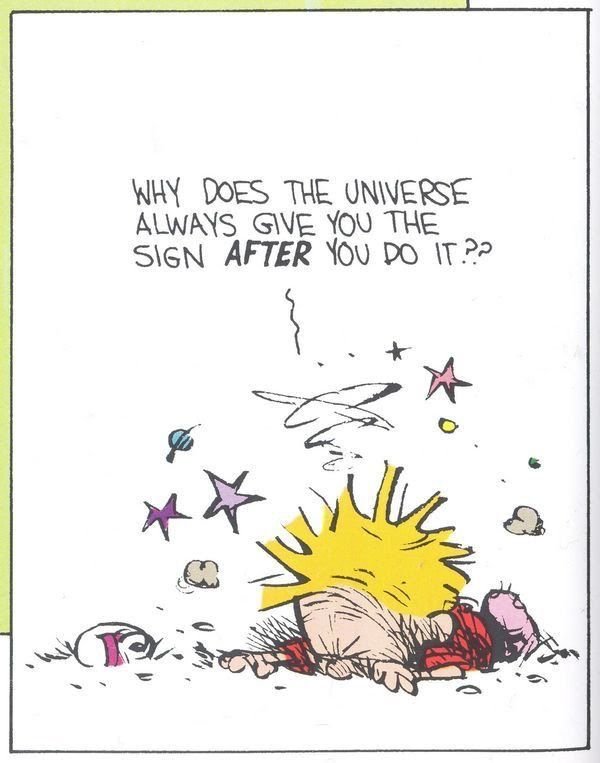

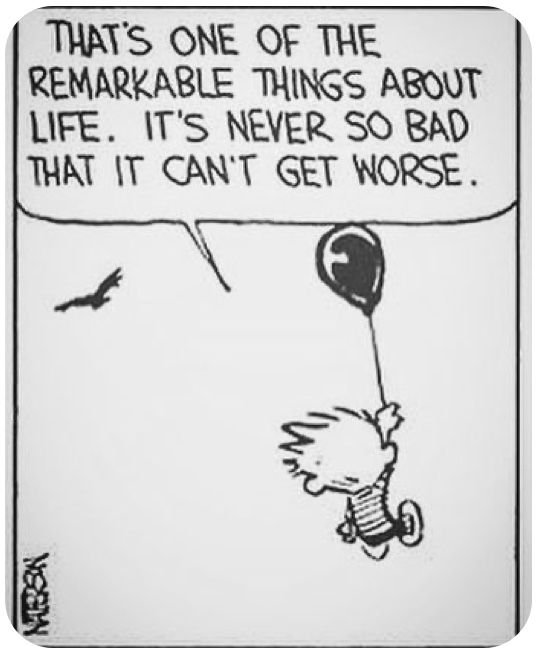

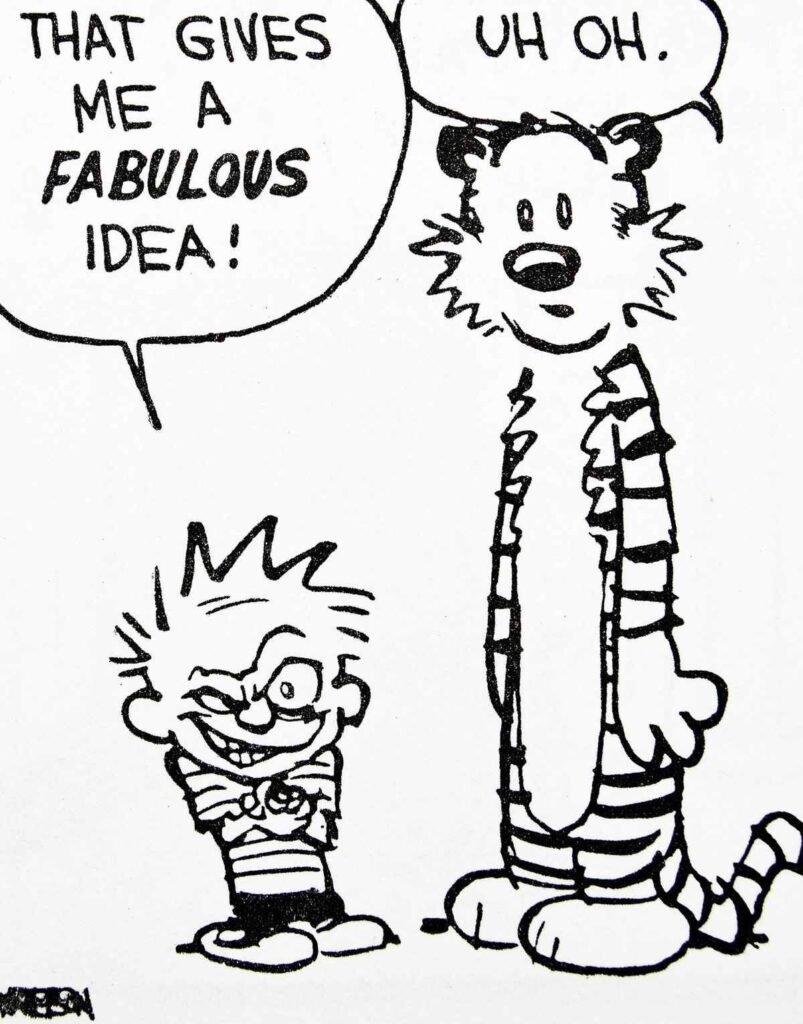

For anyone who grew up flipping through the daily newspaper’s funny pages, Calvin and Hobbes was more than just a comic strip. On the surface, it was the story of a mischievous six-year-old and his wise, stuffed-tiger-best-friend. But if you ever found yourself stopping to stare at a panel long after you finished laughing, you know that Bill Watterson’s masterpiece was something else entirely. It was a bittersweet reflection on life, a philosophical debate disguised as a cartoon, and sometimes, it was surprisingly heartbreaking.

While Calvin spent most of his time evading his babysitter or trying to blast Susie Derkins with a snowball, the strip frequently dipped its toes into waters that were deep, dark, and undeniably profound. It tackled existential dread, the anxiety of growing up, and the struggle to find meaning in a world that often seems too big to understand. Let’s take a closer look at the moments when Calvin and Hobbes stopped fooling around and started reflecting on the human condition.

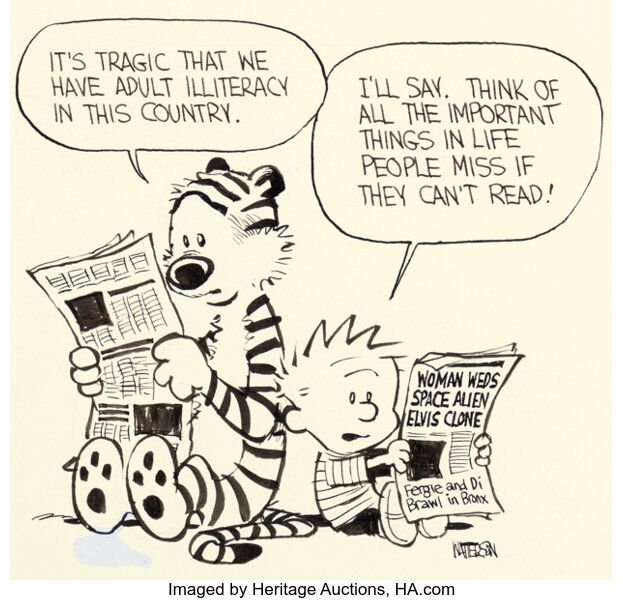

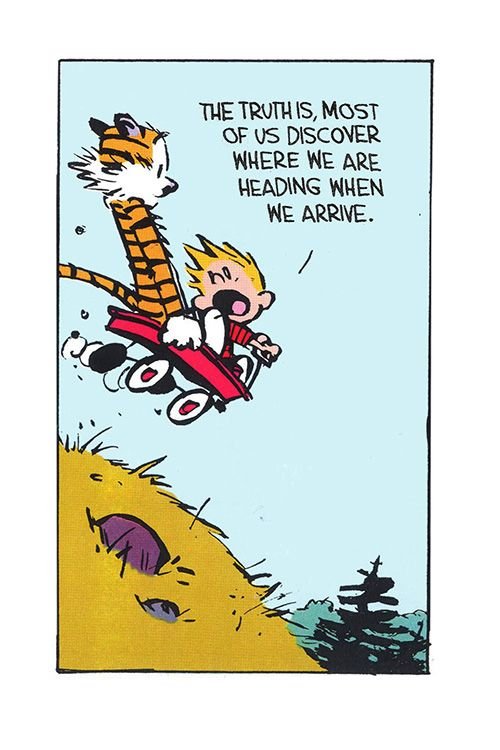

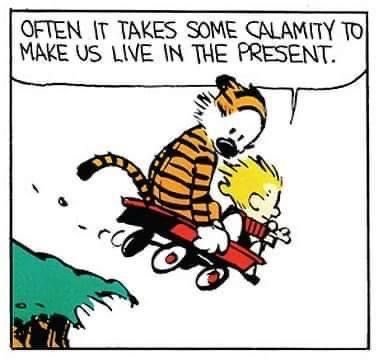

10+ Calvin and Hobbes Comics

Image Credit : Bill Watterson

#1

#2

#3

#4

#5

#6

#7

#8

#9

#10

The Terrifying Reality of Growing Up

One of the most persistent shadows hanging over Calvin’s head is the vague, terrifying concept of the future. Like many children, he lives completely in the moment, so the idea of having to plan for tomorrow—let alone adulthood—feels like a prison sentence. This isn’t just played for laughs; it often borders on genuine anxiety. We see Calvin lying in bed, staring at the ceiling, suddenly struck by the thought that he will eventually have to get a job, pay taxes, and be responsible. To him, this isn’t just growing up; it’s a slow death of everything fun .

This fear is so powerful because it’s so universal. Watterson captures that specific childhood dread where the carefree days of summer feel endless, yet there’s a nagging whisper that they won’t last forever. In one memorable strip, Calvin laments to Hobbes that “There’s never enough time to do all the nothing you want.” It’s a line that sticks with you because it perfectly summarizes the luxury of childhood and the sadness of knowing it’s finite . The “nothing” he speaks of—exploring the woods, sledding down a hill, just being—is actually everything.

The strip rarely shows adults as happy. Calvin’s dad trudges off to a job he doesn’t seem to love, and his mom is often left cleaning up messes. This is the world Calvin sees waiting for him, and it terrifies him. His various fantasies, like being Spaceman Spiff, aren’t just games; they are desperate escapes from the mundane destiny he sees laid out before him. He doesn’t want to grow up because the adults he knows don’t seem to be having any fun, and that is perhaps the darkest realization a child can have .

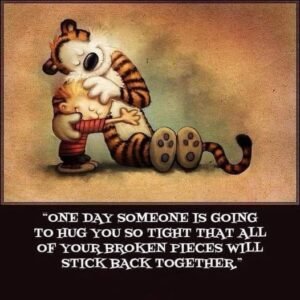

Yet, in these moments of fear, Hobbes is always there. He doesn’t offer easy answers or fake reassurance. Instead, he listens, and his quiet presence reminds Calvin—and the reader—that some things, like true friendship, might just survive the terrifying transition into adulthood. The fear is real, but so is the comfort of having someone by your side to face it.

The Philosophy of Life and the Void

Bill Watterson didn’t shy away from big ideas. In fact, he named his characters after two famous philosophers—John Calvin and Thomas Hobbes—setting the stage for a comic that would regularly ponder the meaning of existence . This wasn’t just about a boy asking “why is the sky blue?” It was about a boy asking “why are we here?” and “what happens when we die?” These heavy topics were often discussed during the quietest moments, usually while Calvin and Hobbes were sailing down a hill on their wagon or trudging through the deep snow .

The snow, in particular, served as a perfect backdrop for these philosophical journeys. As they flew down a hill, with the cold wind biting their faces, Calvin would shout his theories about the universe over his shoulder. It was in these moments of perceived danger and physical vulnerability that his mind opened up to the biggest questions . He wondered if their joyride meant anything if no one else was there to see it, touching on the philosophical idea that experiences require an audience to hold value.

Sometimes, the profound moments came from Watterson’s satire. Calvin’s snowmen weren’t always funny; sometimes they were grotesque, suffering, and melting—a darkly humorous commentary on the human condition and the absurdity of existence. He would create scenes of “The Torment of Existence Weighed Against the Horror of Nonbeing,” which is a hilarious title for a comic strip but also a shockingly heavy concept for a six-year-old to grapple with .

What makes these moments so resonant is that they are never resolved. Calvin asks the questions, Hobbes offers a simple counterpoint, and then they go inside for hot chocolate. Watterson suggests that we don’t need to have all the answers. The act of questioning, of exploring the “why” with a trusted friend, is perhaps the most meaningful thing we can do.

Confronting Loneliness and the Nature of Reality

Perhaps the most profound and debated aspect of Calvin and Hobbes is the nature of Hobbes himself. To the world, Hobbes is a stuffed tiger, a lifeless doll that Calvin drags around by the tail. But to Calvin, and to us, he is very much alive. This duality is the engine of the strip, but it also raises a poignant question: Is Hobbes real, or is he just a symptom of a lonely child’s imagination? Watterson masterfully leaves this ambiguous, inviting readers to choose which version of reality is “truer” .

This ambiguity hints at a profound loneliness. In a world of adults who don’t understand him and classmates who bully him, Calvin has created a world where he is never alone. Hobbes pounces on him when he gets home from school, leaving scratches that even Calvin’s parents can see, blurring the lines between reality and imagination . Is the tiger real, or is Calvin’s imagination so powerful that it manifests physical consequences? The strip never tells us, and that silence is where the depth lies.

The tragedy here is subtle. If Hobbes is just a toy, then Calvin is navigating the complexities of life completely alone. Every deep conversation, every shared adventure, every moment of comfort is a solo act. This reading makes the strip incredibly sad, transforming it into a portrait of a brilliant, isolated child coping with a world he finds difficult to navigate . His fantasies aren’t just fun; they are survival mechanisms.

However, choosing to believe that Hobbes is real is an act of faith in the power of childhood itself. Watterson seems to argue that the imagination isn’t just an escape from reality, but a way of enhancing it. By refusing to break the magic, the comic suggests that the connections we make, even imaginary ones, are valid and essential. Hobbes is the voice of reason, the conscience, and the best friend Calvin needs. Whether he is stuffed or alive almost misses the point; what matters is the profound impact he has on Calvin’s life.

Leaving the Party Early: The Final Goodbye

All good things must come to an end, and Calvin and Hobbes ended on its own terms. Bill Watterson famously retired the strip in 1995 at the height of its popularity, walking away from millions of dollars in merchandising deals to preserve the integrity of his creation . This decision itself speaks volumes about the themes of the strip: that some things are more valuable than money, and that knowing when to leave is a form of wisdom. The final sequence of comics is a masterclass in bittersweet beauty.

The last few days of the strip are a slow, deliberate goodbye. There is no huge farewell party, no final villain to defeat. Instead, we see Calvin and his dad sledding together, a rare moment of pure, wordless connection . Calvin’s dad, usually buried in his newspaper, takes the time to go outside and play. It’s a quiet reminder of what truly matters, a lesson that the strip had been teaching all along.

The final panel of the last strip is famously simple. It shows Calvin and Hobbes zooming downhill on their sled, fresh snow falling around them. Calvin shouts back to Hobbes, “It’s a magical world, Hobbes, ol’ buddy… Let’s go exploring!” . There is no conclusion, no summary of their adventures. They simply ride off into the white expanse, together. It is hopeful, joyful, and profoundly sad all at once. They are frozen in time, forever exploring, forever six years old, while the reader is left behind to grow up.

This ending is the strip’s final and most profound moment. It acknowledges that life is a series of moments that slip away, that childhood is fleeting, and that the best we can do is to embrace the magic while we can. The blank, white panel at the end isn’t an ending; it’s an open door. It’s an invitation for the reader to grab their own sled, find their own Hobbes, and keep exploring. In the end, Calvin and Hobbes isn’t just about a boy and his tiger. It’s a reminder to hold on to wonder, to question everything, and to always, always go exploring.