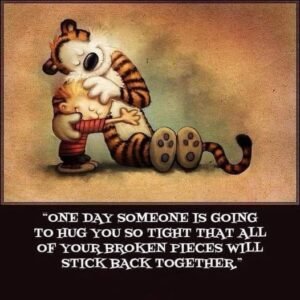

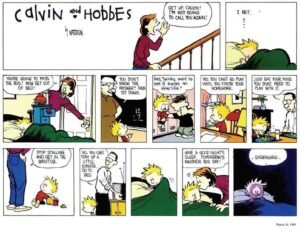

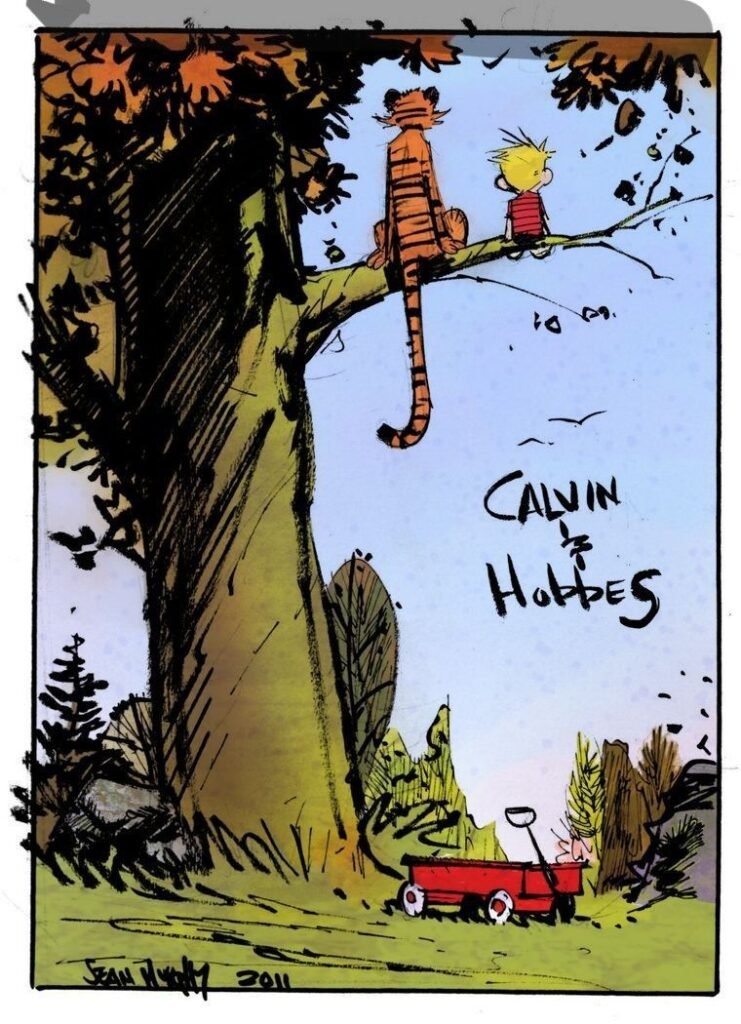

For anyone who grew up reading the funny pages, some comic strips are just funny. Others are smart. But every so often, there comes a strip that feels truly magical. “Calvin and Hobbes” is exactly that kind of magic. Created by Bill Watterson, this comic ran in newspapers from 1985 to 1995, and even though it ended nearly three decades ago, it remains one of the most loved comics in history . While other strips have made us laugh with witty one-liners or silly situations, Calvin and Hobbes did something different. It took readers inside the mind of a six-year-old boy and made us believe, even just for a moment, that a stuffed tiger could come to life. It showed us that the world is far more interesting if you just look at it a little differently. This is why, when it comes to showcasing the power of a child’s mind, no other comic has ever come close.

What makes this strip so special is that it treats imagination not just as a funny gimmick, but as a necessity. For Calvin, his daydreams aren’t just a way to pass the time; they are a way to survive the boredom of school, the annoyance of chores, and the confusion of being a small person in a big world. Whether he is turning his cardboard box into a time machine or his wagon into a space shuttle, Watterson never makes fun of Calvin for these dreams. Instead, he celebrates them. He invites the reader to step into that world where the lines between what is real and what is imagined aren’t so clear. And at the center of it all is Hobbes—the tiger who is a lifeless toy to everyone else, but a loyal, wise, and sometimes sarcastic best friend to Calvin .

Image Credit : Bill Watterson

#1

#2

#3

#4

#5

#6

#7

#8

#9

#10

More Than Just a Toy

The single most important element of the strip’s exploration of imagination is Hobbes himself. Bill Watterson made a brilliant choice early on: he never clearly explained Hobbes. We see him one way when it is just Calvin in the panel, and another way when a third character, like Calvin’s mom or dad, walks into the room . To Calvin, Hobbes is a giant, walking, talking tiger who loves to pounce on him when he comes home from school. To everyone else, Hobbes is simply a stuffed animal sitting on the couch.

This ambiguity is the heart of the magic. Watterson never ruins the illusion by having an adult see Hobbes move. He lets the reader decide what is “really” happening. Professor William Kuskin from the University of Colorado notes that this “ambiguity invites readers to participate in the magic” . We are not just watching Calvin’s imagination; we are inside of it. We see the world the way Calvin sees it. This makes Hobbes feel real to us, the readers, in a way that a typical “imaginary friend” in other stories does not. He has his own personality, his own sense of humor, and he often acts as the voice of reason that Calvin desperately needs to hear.

By keeping Hobbes’s reality a mystery, Watterson shows us how imagination works in real life. When children play, their toys are alive. They have conversations with them, go on adventures with them, and love them deeply. Watterson honors that childhood experience by drawing it exactly as it feels to the child. He doesn’t condescend to the reader by putting a label on it. He simply shows us the world through Calvin’s eyes, and in doing so, he reminds us of a time when our own toys had personalities and our own bedrooms were portals to other dimensions. It is this respectful treatment of childhood fantasy that makes the strip resonate so deeply with adults who look back on their own youth with fondness .

Turning Boredom into Adventure

Another way the strip captures the magic of imagination is through its depiction of everyday life. Calvin is not a kid who goes on exotic vacations or lives in a fantasy world full of wizards and dragons (at least, not usually). Instead, he lives in a very normal, middle-class suburban neighborhood. He has a mom who tells him to clean his room, a dad who reads the paper, and a teacher named Mrs. Wormwood who just wants him to pay attention. This setting is important because it is so relatable. Most of us grew up in houses just like Calvin’s.

Calvin’s imagination is his escape route from the boredom of this normal life. A rainy day becomes an opportunity to build a “transmogrifier” out of a cardboard box so he can turn Hobbes into a elephant. A trip to the bathtub becomes a deep-sea diving expedition or a fighter jet dogfight. A simple walk to the kitchen for a glass of milk can turn into a slow-motion trek across a desert landscape. Watterson’s art style shifts dramatically during these scenes. The backgrounds become wilder, the perspectives become more dynamic, and the energy of the panel explodes . This visual shift lets the reader feel the rush of excitement that Calvin feels when he breaks free from the chains of the ordinary.

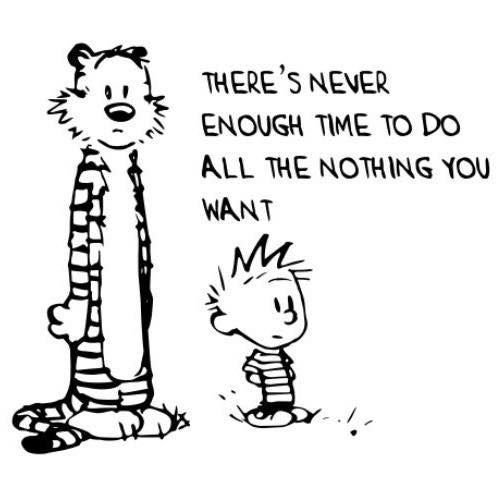

This is where Calvin and Hobbes surpasses other comics that rely on situational humor. The strip argues that imagination isn’t just about having fun; it’s a tool for survival. The world is full of rules, routines, and demands that can suck the joy out of life. Calvin’s imagination is his shield against that. He doesn’t just complain about having to walk to school in the snow; he imagines he is a fearless explorer trudging through the arctic wasteland. By doing this, Watterson suggests that the ability to reframe our problems through creativity is a skill we should never lose. He makes boredom look like the starting point for the greatest adventures of all .

Questioning Life’s Big Questions

While the strip is hilarious, it also has a depth that is rare for any art form, let alone a four-panel daily comic. Because Calvin views the world through his imagination, he is able to ask big questions that other characters don’t even think about. He wonders about the nature of reality, the existence of God, the meaning of life, and why we have to spend so much time on homework when we could be outside making snowmen . These aren’t just jokes; they are genuine philosophical inquiries framed by the mind of a child.

Hobbes is usually the one who listens to these rants and offers a calm, sometimes cynical, response. Their conversations are essentially philosophy 101 discussions dressed up in the clothes of a six-year-old and a tiger. For example, Calvin might argue that the universe is too big to comprehend, so he might as well just watch TV. Hobbes will then point out the flaw in his logic, forcing Calvin (and the reader) to think a little harder. The strip references real philosophers—Calvin is named after theologian John Calvin, and Hobbes after philosopher Thomas Hobbes—but it makes their complex ideas accessible to everyone .

By filtering these big ideas through Calvin’s imagination, Watterson shows that curiosity is a form of magic. It is the drive to imagine things that we cannot see—like the vastness of space or the concept of infinity—that makes us human. Calvin doesn’t just accept the world as it is presented to him by his parents or teachers. He questions it, twists it, and re-imagines it in his own terms. This constant questioning is the engine of the strip’s humor and its heart. It tells us that a rich inner life is just as important as the outer life we live. We may not have all the answers, but the joy is in the “exploring” .

Why the Magic Remained Pure

Finally, one of the biggest reasons Calvin and Hobbes captures imagination so well is because Bill Watterson protected it fiercely. In the 1980s and 90s, successful comics were often turned into merchandise. Charlie Brown became a plush doll, Garfield appeared on car windows, and the Smurfs were turned into everything from toys to cereal. There was immense pressure on Watterson to do the same. He could have made millions of dollars by allowing Calvin to be printed on T-shirts, coffee mugs, and birthday cards. But he said no .

Watterson believed that licensing the characters would ruin the magic. If Hobbes appeared as a stuffed doll in a store, it would answer the question that the strip so carefully kept open. Hobbes would no longer be a real tiger in our imaginations; he would just be a product on a shelf. Watterson famously fought his syndicate to keep Calvin off of merchandise, leaving an estimated $400 million on the table to protect the integrity of his work . This decision was almost unheard of in the industry, but it is a huge reason why the strip still feels so personal and timeless today.

Because there were no cheap cartoon specials or mass-produced toys, the magic of Calvin and Hobbes stayed exactly where it belonged: in the pages of the comic strip and in the minds of its readers. The characters never became overexposed or diluted. They remain exactly as Watterson drew them, frozen in their snowy final frame, heading off on another adventure. This artistic purity means that when we read the strip today, we experience it the same way readers did in 1985. We are invited to use our own imaginations to bring Hobbes to life, just as Calvin does. Watterson trusted his readers to be co-creators of the magic, and that trust is what makes the bond between the reader and the strip so special .

Conclusion

In the end, Calvin and Hobbes remains the gold standard for imagination in comics because it never forgets what it feels like to be a kid. It understands that a pile of snow isn’t just a pile of snow—it’s a potential masterpiece of sculpture or an iceberg in a frozen ocean. It understands that a best friend doesn’t have to be human to be real. Bill Watterson created a world where the imagination is the most powerful force there is, capable of transforming boredom into adventure, confusion into philosophy, and a stuffed tiger into a loyal companion for life. Other comics have made us laugh, but Calvin and Hobbes made us remember. It reminded us that the world is a magical place if we only choose to look at it that way. And as Calvin himself said, if those golden afternoons are finite, it’s better to grab your sled and your best friend and go exploring while you can